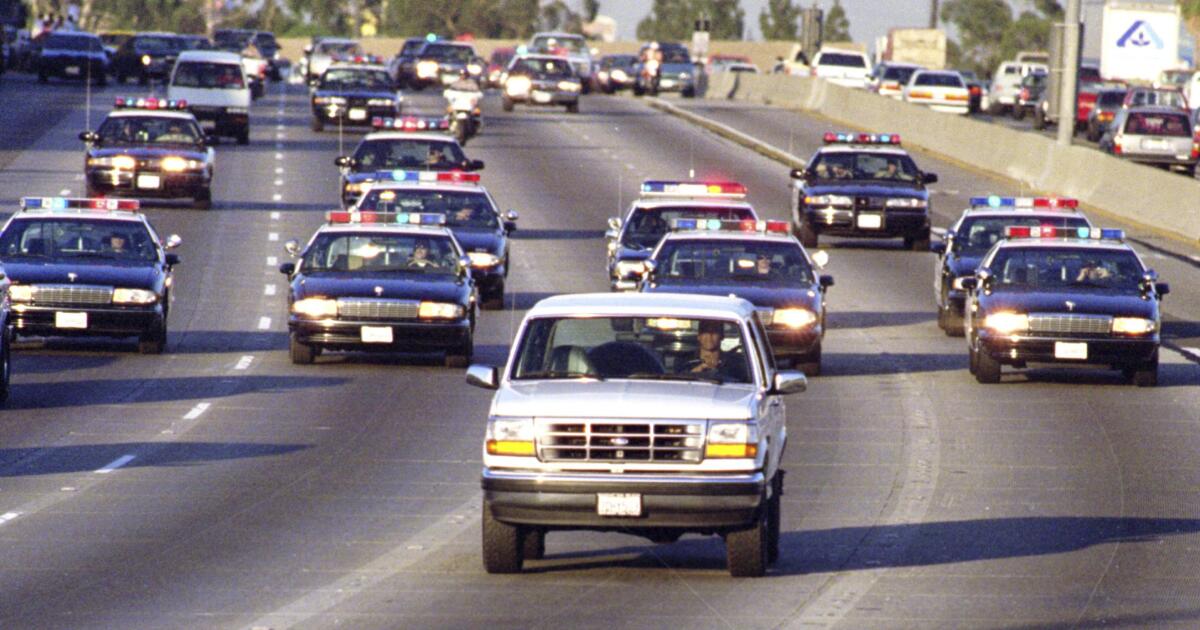

Following the televised event of O.J. Simpson fleeing from police in a white Ford Bronco on June 17, 1994, abusers in Los Angeles began using a disturbing new threat: “I’m gonna O.J. you.” This threat was used as a form of intimidation and silencing towards their victims, as stated by Gail Pincus, executive director of the Domestic Abuse Center in Los Angeles. Survivors of abuse expressed fears of becoming the next Nicole, flooding hotlines and shelters for help. The public was captivated by the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman, shedding light on the deadly reality of domestic violence for women. Domestic violence statistics became more widely known, prompting legislative changes and the passing of the Violence Against Women Act in 1994. The O.J. Simpson case brought domestic violence to the forefront of public awareness, leading to increased support and resources for survivors.

‘We need to push this now’

Peace over Violence executive director Patti Giggans watched the Bronco chase with a plan, seeing it as an opportunity to raise awareness about domestic violence. The case highlighted the issue of domestic violence and brought advocates into the spotlight, leading to changes in laws and increased support for survivors. Advocates seized the moment to push for legislative changes and ensure that the tragedy led to tangible benefits for survivors.

‘People didn’t know anything’

The O.J. Simpson trial exposed the public’s lack of understanding about domestic violence, prompting advocates to educate and raise awareness about the seriousness of the issue. Despite progress in legislation and public awareness, there was still a gap between what the public knew and what the legal system acknowledged in cases of domestic violence.

Six months after Simpson was acquitted, California added Section 1109 to the Evidence Code, allowing uncharged conduct and other evidence of prior abuse to be shown to jurors in similar cases.

The trial also shined a spotlight on DNA evidence, then a scientifically established but publicly suspect technology.

“It was like mumbo-jumbo to the public at that point,” Pincus said.

Today, DNA evidence is critical to many domestic violence prosecutions because it gets around the reliance upon “he-said, she-said” narratives that long hampered battery cases.

Without DNA, “it came down to who jurors believed: the hysterical victim who jumped all over the place telling her story or refused to testify out of fear, and the abuser who was calm and seen as a nice guy,” Pincus said.

With evidence handling under a microscope, advocates were able to push for reforms in how the LAPD managed rape kits, eventually leading to the creation of a new DNA crime lab.

“The case really did spearhead legislation that started expanding resources,” said Carmen McDonald, executive director of the Los Angeles Center for Law and Justice.

Still, some say the changes are more surface-level than substantive.

“These wonderful changes that were supposedly wrought by the mistakes made during that trial are not anything that I’ve benefited from, and they’re not anything any woman I know has benefited from,” said Gurba, the author and survivor. “If it’s prosecuted, most domestic violence is prosecuted as a misdemeanor. So the state sees our torture as a petty nuisance.”

Now, she and other advocates fear gains made since the trial could soon be erased.

‘All that we built since O.J. can go away’

California is poised to lose tens of millions in funding for domestic violence programs this year, a 43% cut that threatens critical infrastructure including emergency shelter, medical care and legal assistance to survivors, according to the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence.

Programs for at-risk populations already are stretched thin under the existing budget, survivors and advocates say.

“When I tried to enter a shelter when I was escaping domestic violence, I couldn’t get into one because they were all full,” Gurba said.

Now, those already overburdened services could disappear.

“It’s about to fall apart,” Giggans said. “All that we built since O.J. can go away.”

Advocates fear the cuts could create a cascade effect across the state.

“Domestic violence impacts every single community and population; it’s across every field,” McDonald said. “It’s immigration, it’s schools. The loss of funding impacts [other] services that are out there for folks who need help.”

For example, data show domestic violence is a leading cause of homelessness. According to a survey released last summer by the Urban Institute, nearly half of all unhoused women in Los Angeles have experienced domestic violence, and about a quarter fled their last residence because of it.

For Gurba, the looming cuts are yet more evidence of how little has truly changed since the 1994 slayings.

“I don’t think there was a revolution in how domestic violence survivors are treated thanks to that murder — that’s a myth,” she said. “The rhetoric may have changed, but the treatment is still the same behind closed doors.”