Myanmar currently has two national-level matriculation examinations: one administered by the Ministry of Education under the State Administration Council (SAC) military junta, and the other conducted by the Ministry of Education, National Unity Government (MOE, NUG), a parallel government established on April 17, 2021, following the February 2021 military coup.

The matriculation examination serves as the entry point for high school students to pursue further studies at one of Myanmar’s 170+ universities. Students take this exam upon completing Grade 11, the final year of high school, typically held once a year in March. As the sole criterion for university admission in Myanmar, parents and students invest heavily in preparing for the matriculation examination to secure future career opportunities.

The history of the matriculation examination dates back to the 1962 military coup, which ushered in a period of state socialism and prioritized science subjects in the education system. This led to the enactment of the 1964 University Administration Law, centralizing the administration of universities and limiting their autonomy in student recruitment. Additionally, the exam results became the primary factor in assigning students to universities and specializations, favoring science-related fields.

Under the 1973 University Administration Act, universities have no control over the admission process, with the Department of Higher Education assigning students based on their matriculation exam scores. This underscores the significance of the exam, prompting heightened security measures and garnering public attention due to associated events, rumors, and controversies.

In the aftermath of the coup, the SAC’s education authorities faced challenges conducting the 2021 matriculation examinations due to nationwide protests, civil disobedience movements, and COVID-19 disruptions. The military’s education ministry attempted to politicize the exam by announcing the 2022 application process, sparking public debate and rumors of coercive tactics to compel student participation.

Related

Farmers, Facebook and Myanmar’s coup

New analysis shows how a surge of online resistance in the countryside faded amid fear and self-censorship.

The NUG responded to SAC’s exam announcement, declaring the illegitimacy of education activities conducted by the military junta. The NUG’s education ministry highlighted the exam’s politicization and called for boycotts, emphasizing the lack of international and public recognition for SAC.

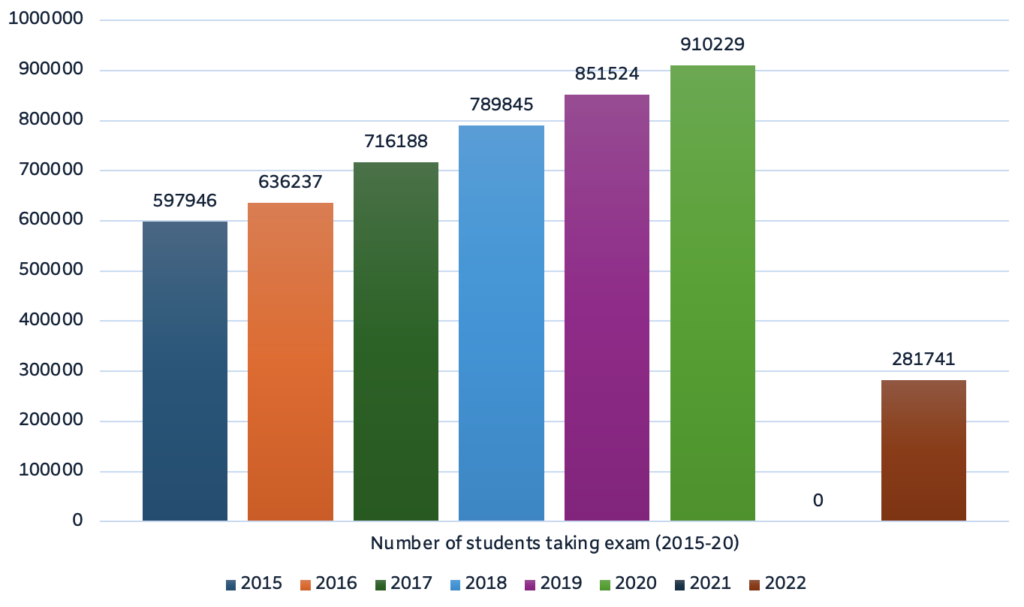

Statistics from SAC’s 2022 matriculation exam underscored low participation rates, with only 30% of registered students taking the exam. This trend indicated widespread support for the civil disobedience movement and resistance to military administration.

Figure 1: Number of students taking matriculation examination, 2015–2022

(Source: author’s calculation based on Ministry of Education [SAC] release)

The NUG grappled with the implications of the low exam turnout and deliberated on strategies to counter SAC’s exam dominance. Policymakers within the NUG expressed concerns about student futures and the NUG’s legitimacy if they failed to provide alternative educational opportunities.

The prevailing political climate prompted the NUG to prioritize organizing a rival matriculation examination, aligning with public sentiment and asserting its authority amidst the ongoing crisis.

The national mood of post-coup Myanmar regarding the military-conducted matriculation examination is reflected in the country-wide civil disobedience movement (CDM). under which civil servants refused to work under the military and people were not cooperating with its administration.

Although the campaign was first kicked off by healthcare workers, teachers and administrative staff in the education sector shared the majority of the CDM population. Initially, it is estimated that more than 300,000 education workers participated in CDM. As of April 2021, according to ISP Myanmar, the military has released that more than 27% of primary and secondary education staff and 56% of tertiary education staff are absent at their workplace—meaning that they have joined the CDM.

Several universities declared themselves as CDM universities and constituted ‘Interim University Councils’ to manage the affairs of the university themselves. Primary and secondary education staff, constituting township education boards, refusing to follow military orders. As of Oct 2021, 279 township education boards (out of 330 townships across the country) and 235 university councils (out of 297 universities across the country) are affiliated with the NUG.

Meanwhile, a majority of the student population in primary, secondary and tertiary education refused to attend the schools reopened by the military. Only a quarter of 12 million primary and secondary students and very few university students enrolled for the new school year in June 2021, either due to showing their solidarity with CDM or inadequate COVID-19 prevention measures prepared by military administration at school.

This country-wide CDM caused the NUG not only to provide education services but also to pay good attention to the military’s education policies and to counterattack if necessary. This is because such an action could fuel the momentum of CDM and accumulate domestic support for the NUG. By the time the military’s education ministry announced the matriculation examination as aforementioned, the NUG were alarmed to focus on it and to conduct their own nationally standardised examination.

In addition to the national mood, the support of the interest groups encourages the NUG to prioritise conducting a rival matriculation examination. Some interim university councils which are affiliated with MOE, NUG, have publicly announced that the university would not recognise the matriculation examination conducted by SAC in 2022 and would not allow enrolling those students taking the 2022 exam.

For instance, more than 20 councils of technological universities and students’ unions released statements unrecognizing the examinations under SAC and have urged the parents and students not to sit for the examination as a means to against the military regime and keep continue the country-wide civil disobedience movement. Such support from its affiliated university councils and student unions pressed the NUG to initiate a rival examination to counter the military administration. Moreover, it is likely that the cabinet of NUG assumed that conducting such matriculation examination would serve its own political interests, fuelling the continued nationwide CDM and thereafter increasing its legitimacy domestically.

A Policy Window

Policy entrepreneurs — people who desire to invest his/her resources in return for the future policy they favour, are significant in the Myanmar examination case. They are invisible participants— mostly groups of scholars, educationists and experts in assessment and examination. They boycotted the military’s educational activities, anonymously affiliated with the NUG’s education ministry, and were involved in its different education activities.

They have put their resources such as time, knowledge and skills into different NUG education activities as a way to show their opposition to the military coup. Those experts in assessment and examination helped draft an assessment policy for the NUG’s home-based education program. Their efforts have been a significant factor in pushing the NUG to consider conducting its own matriculation examination. Before the military planned to conduct the matriculation examination, they sought to advocate that the NUG conduct or at least consider conducting the matriculation examination. For them, it is believed that the NUG education ministry needed to be proactive in considering conducting a rival matriculation examination as the military would take political advantages from the exam. When the military decided to conduct the 2022 matriculation examination in November 2021, it was a politically favourable time or a policy window for those assessment academics to push their pet proposal of developing a NUG matriculation examination.

Moreover, my analysis of the policy documents also suggests that the assessment experts developed the NUG’s matriculation examination policy proposal to pertain to some criteria such as technical feasibility, congruence with the values of community members and anticipation of future constraints such as budget and receptivity of the public and politicians amidst political instabilities. First, the assessment policy came along with two-hour-long multiple-choice questions which are efficient in marking, and relevant for interim resistance governments like MOE, NUG to administer well. In the past, the matriculation examination had several essay-type questions which required thousands of teachers to gather in a particular university for several days to mark and compile data. This could not be the case for the NUG’s examination because it is based on multiple-choice items which could be easily marked.

Furthermore, by considering the NUG’s limited on-ground education services and the proximity of the students to conflict, the policy proposed both internet-based and paper-based assessments at on-ground assessment centres. It allows students to take the examination at multiple examination periods within a year—in 2023, in February and August—at their convenience.

In addition, a big shift from military matriculation is that it guaranteed to assess the higher-order thinking such as application, analytical thinking and creative problem-solving skills of Bloom’s Taxonomy with a competency-based grading system. This is in congruence with the values of community members, as the education community in Myanmar has been long for a paradigm shift in assessment in Myanmar from memorisation-based to competency-based assessment during the country’s education reform period during 2011–2021. In an interview, one community mathematics teacher mentioned that he is receptive to the question type of the NUG’s exam, especially for the mathematics subjects, because, for example, in Geometry, the exam does not require students to jog down the name of a theorem exactly as in the before-coup exam, which renders memorisation instead of logical reasoning.

Most importantly, it is also deemed that the matriculation examination proposal anticipated the future constraints of public acceptability.

In an interview with a person from a township education board, constituted in the post-coup period, he mentioned that the people who are working on on-ground education in the conflict-affected areas accepted that they need a matriculation exam which is not administered by SAC.

It is important to note here that some of the policy entrepreneurs around the NUG ministry of education were also involved in township education boards, and, for them, it means that a rivalry examination would fill this gap and could potentially increase their domestic legitimacy. Hence, the policy solution attached to the requirement of examination for more than 70% of the high school student population who boycotted the SAC’s exam and countering SAC’s exam finally led to opening a policy window for the NUG to conduct its own matriculation examination.

The impact on students

Ultimately, students are those most impacted by how Myanmar’s education system has been affected by the 2021 coup. The military killed and detained teachers and students, and used schools and university campuses as bases for military operations. It then extended its manipulation to matriculation examination through politicisation. To counter such a problem, when the political climate is favourable and policy solutions are available, the NUG’s education ministry has initiated matriculation examinations as part of its political battles with the SAC.

Both the SAC and NUG exams have good and weak points. Firstly, taking SAC’s exam is incompatible with society’s values and the CDM. Parents across Myanmar boycotted the military-led schooling and did not let their children take the matriculation examination to show their solidarity with the country-wide CDM or because they do not believe in the quality of teachers under the military education system. On the other hand, taking the NUG’s exam might lead to security concerns and to situations where future education pathways with the future recognition of NUG-issued credentials being uncertain As a result, the students face ambiguity about how to proceed with their educational pathways. (At the time of writing, the NUG’s education ministry has conducted their version of the matriculation examination twice, and 16 universities affiliated with them recently welcomed the new students.)

Such a situation also exacerbates the disparity among the students. Some students, who could afford it, decided to prepare for internationally recognised certificates such as GED and IGCSE to avoid the dilemma. Meanwhile, others drop out of school, take up arms, or flee due to conflict in their areas. As a consequence, the students lose their hopes and future, leading to the deterioration of human capital and the future development of Myanmar.